Fake Domain Wire Transfer Scheme 2015-12-09

A new controller reported for his first week of work at ABC Tire Company anxious to prove

that his new employer had hired the right person. In his first week, he received an email from the

company CEO with the instructions: “Process a wire of $205,250.29 ASAP to the below account

information. Code it to professional services. Send me the confirmation when completed. Thanks,

Gary, CEO.”

The new controller promptly followed his CEO’s instructions and completed the wire. When

he approached the CEO the following day, he smiled and said, “Sir, I took care of that wire transfer

you requested.” The CEO responded, “What wire transfer?” To his horror, the new controller

realized he had been a victim of an Internet fraud scheme. The email had come from a fake, cleverly

disguised corporate domain…

The scheme had three unique traits:

1. it uses a fake email domain intentionally designed to fool the recipient into thinking it came from his or her company;

2. the victim companies, rather than the banks, suffer the full loss of the funds; and

3. it has an alarmingly high success rate, a sure sign that it will be a growing trend.

The details of this scheme and the high success rate suggest that the fraudsters are assisted by insiders.

Through a phishing attack or social engineering, the fraudsters gain control of a corporate email box and correctly identify and

impersonate a corporate official authorized to direct the transfer of funds by wire. Once in control of the

email box of the relevant executive, the fraudsters wait for the optimum time to execute the scheme:

emailing the unassuming accounting staffer in the executive’s name to request the wire transfer. They

typically use a fake domain—usually obtained from a foreign vendor—that is very similar to the company’s

actual domain so that it is not suspicious to the recipient, and the email is not detected by the executive

they are impersonating. The fraudsters have the payment initially directed to a foreign bank account, and

then redirect the funds several times until the money reaches a bank located in a known tax haven, making

retrieval and/or prosecution difficult, if not impossible. Recent cases have seen funds end up in domestic

accounts as well.

Successful fraudsters empty the accounts within hours to just days after the wire transfers, so the only way

for a victim company to retrieve the funds is to act quickly to recall the transfer and freeze the account.

Once the transfer is complete, so is the financial loss to the company, while the banks remain unscathed.

Prevention is the only true protection: strong vendor protocols, financial controls and staff communication

and training are essential to thwarting these fraudsters.

It’s well known that fraudsters are experts at procuring information needed to execute their

schemes through research, social media sites, and social engineering. The job of a fraudster is to

steal something of value from someone else. It is their only job; it’s what they do – all day, every

day. Fraudsters know that the United States is a target-rich environment of small and medium size

companies that have inadequate controls to prevent an intrusion or fraud. For example, a simple

search on social media sites will often supply the names, titles and responsibilities of current and

former employees of a targeted company, from C-suite executives to functionaries in the accounts

payable department.

When social media is unhelpful, calls to employees by fraudsters, who are expert social

engineers, can produce the identities of personnel such as the CFO, Controller, and accounting staff

members. We have even seen successful schemes in which unsophisticated accounting employees

have given out sensitive business information like wire transfer protocols, bank account details, and

passwords to fraudsters posing as legitimate third parties.

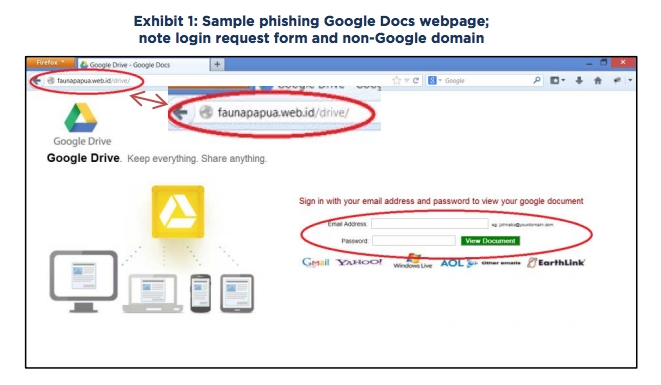

GOOGLE DOCS PHISHING

In the earliest version of the fake domain wire transfer scheme, fraudsters used a phishing attack, a fake Google Docs website, and a fake

domain to execute the fraud on companies that use or allow the use of Gmail, or another web-based email platform. The fraudster, using social

engineering or phishing techniques, induces an employee to open a link to a false website. This website is designed to look like a login page for

Google Docs. The site asks for the employee’s username and password. The URL of the web page is often suspicious to the careful observer

and does not exactly resemble the Google login page. However, recent attacks have leveraged the ability to host the website on Google’s hosting

platform, so the URL seems legitimate, and the web page is a near perfect replica of Google’s login page. (Exhibit 1)

When the employee enters company provided email credentials into the web form and clicks “View Document,” the phishing website

redirects the employee to a page that claims the document cannot be found, but now the employee’s credentials have been sent to the fraudster.

After receiving the user’s login credentials, the fraudster logs into the employee’s email account, occasionally from an anonymizing

service or a foreign country (e.g. Africa or Eastern Europe), and spends a short time in the email box before logging out. The time spent in

the employee’s email box enables fraudsters to learn information pertinent to executing wire transfers within the company and the ability to

read “out-of-office” notifications.

What should you do?

The first step to prevent against becoming a victim is to review wire transfer protocols, both internally and with the bank. Companies must insist that banks have a call back protocol and adhere to it regardless of how difficult it may be to reach the designated official. Internally, companies need to review their controls relating to payments and wire transfers and consider a higher level of authorization for disbursements to first time vendors. For example, this could mean designating an official who “owns” each vendor and requiring that accounting staff contact the appropriate official before transferring funds. Companies also need to arm against phishing attacks and social engineering. Education and training to help employees recognize these techniques is the best defense. For companies that use or allow Google Docs or Gmail, enabling Google’s 2-Step verification, also known as two factor authentication, will prevent an outside party from logging into Google without a requisite authenticator token. However, while a successful attack using Google 2-Step login code has not been reported, fraudsters often change tactics as defenses evolve. A higher barrier to prevent unauthorized access into Google Apps is the use of a third party SSO or SAML provider, such as Ping Identity, Centrify, and others2 . These services allow for a much stronger login system into Google applications, restricting login based on location, device, as well as tokens. Not only do these services increase the complexity required for an attacker to gain access to corporate email, they allow the login portal to be customized, making it difficult for an attacker to anticipate and mimic on their phishing page.

Follow us on twitter, facebook and google plus.

back

Sitetrader 2026

Sitetrader 2026